Hello lovely readers and welcome to Idiot Parade.

I’m back at it with another art history quickie, regrettably not so hot on the heels of previous entries on Robert Gence’s Portrait de chasseresse and Horace Vernet’s Napoléon aux Tuileries. This month we’re crossing the English Channel and the gender gap but staying fixed in the 19th century, partially because I’m sorta-kinda rereading Jane Eyre in lieu of letting my powers of cognition rot in the fields of Instagram Reels for hours at a time. God, I miss having an attention span.

In any case, these monthly art history essays will be free for everybody forever, so please consider subscribing if you like ‘em.

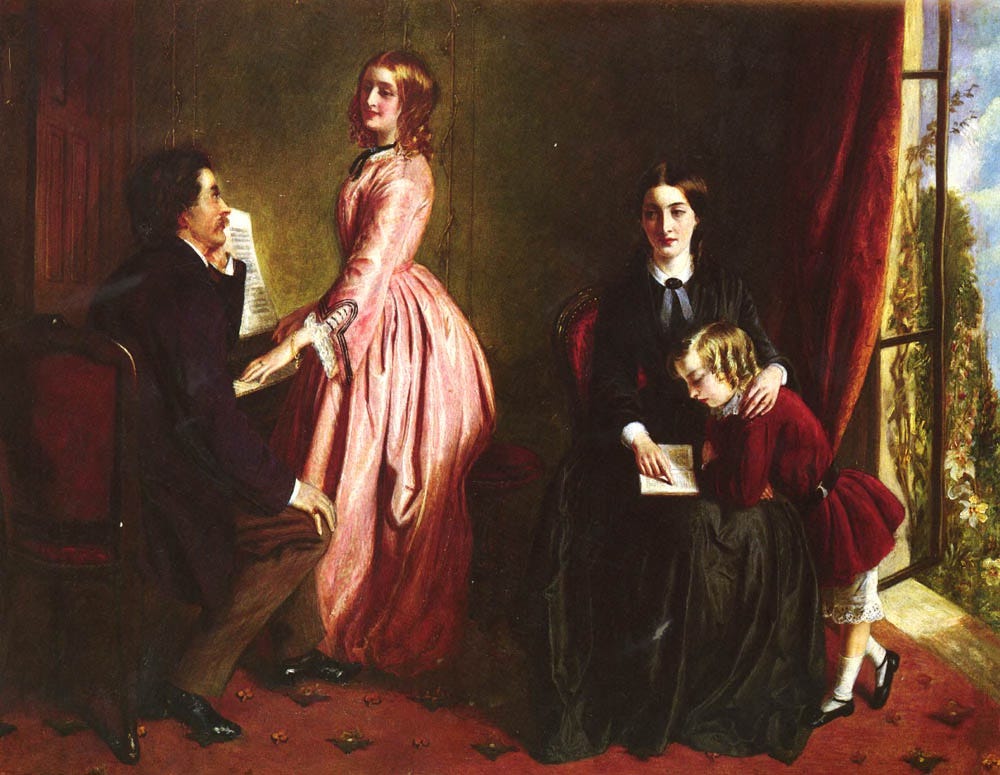

There are few paintings I have viewed in passing more than the right three-quarters of Rebecca Solomon’s The Governess, which adorns the fraying cover of my copy of Jane Eyre. Cut off at the wrist of the male figure, the cover repositions the painting’s titular subject at the center of the image and pits her even more intensely against the lady in pink. The crop job makes it bitchier. Some days I prefer it to the full view.

Rebecca Solomon was born in London in 1832 to a middle-class Jewish family. She was formally trained and politically conscious, broadly concerned with social issues in her work and involved in the successful 1859 petition to open the Royal Academy of Arts to female students. She exhibited throughout her lifetime and enjoyed contemporary acclaim. Upon the debut of her 1858 painting Behind the Curtain she was declared “one of the very best of the female artists” by The Globe and, in 1876, lauded for her “masculine genius for portrait painting” by The Chronicle.

In addition to selling her own paintings, she worked as a copyist, illustrator, and assistant in the studios of John Everett Millais and Edward Burne-Jones, both major figures associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and as agent and assistant to her brother, the painter Abraham Solomon. She never married. No portraits or photographs of her exist.

Solomon painted The Governess in her early twenties following the initial burst of Pre-Raphaelite artistic production in England. Although the vernacular of such images would have been plenty familiar to her, she chose to exclude it from this particular work. Her governess bears minimal resemblance to the standard-issue Pre-Raphaelite woman—a typically mythical, historical, Shakespearean, Arthurian, or biblical figure, and almost always a great beauty.

The governess was nevertheless herself an archetype of Victorian art and a fact of Victorian life, with approximately 25,000 women listing it as their profession in the 1851 census. Each of these women, according to historian Bonnie G. Smith, “personified a life of intense misery,” trapped on the downwardly mobile trajectory of a “single, middle-class woman who had to earn her own living.”1 Lower than her employers but above the other servants, the governess existed in a sort of social limbo, her entwined professional and psychological positions characterized by isolation. For her actual work she was poorly paid, and often left destitute in old age.

Solomon’s painting captures this highly specific emotional reality. This governess is not only free of the debasement of poverty but employed in a home brimming with music and sunlight and familial harmony. Her charge reads quietly and obediently on her lap. A summer breeze wafts through the window, tousling the curtains and caressing her cheek. Her employers have granted her reasonable request to wear mourning dress. And she is a profoundly unhappy woman.

When cropped at the man’s wrist on the cover of Jane Eyre, we reflexively read The Governess as a depiction of the competitive womanly envy Jane at least claims not to feel toward Miss Ingram, Mr. Rochester’s socialite suitress. But uncropped, Solomon’s governess’ gaze appears far less pointed. She’s not even looking directly at the man, for whom there is no competition anyway given how clearly he adores his wife.2

To be clear, the governess is doubtlessly jealous. On this point, Solomon’s composition and contrasts are didactic: pink, frilly, blonde, and smiling versus black, austere, brunette, and tight-lipped. The prevailing theme of this painting is the divide between the haves and the haves-to-work, and the feelings this divide summons within the latter. But Solomon’s governess is also more than just jealous.

This governess exists in relation to everyone else in the room, none of whom regard her. She looks up from the book and past her employer, and she’s struck by a feeling of displeasure and boredom—perhaps a proto-Friedan version of the problem that has no name? Compensated or not, her station produces in her an unnameable misery she cannot attribute to something as obvious as mistreatment or bereavement. When I look at Solomon’s governess I do not necessarily see her coveting a man. I see a woman caught, even momentarily, in an unbearable psychological limbo.

The other governesses of Victorian art lack such emotional nuance. The reasons for their misery are apparent. Richard Redgraves’ The Governess (1854) holds a letter from home containing bad news, and daintily withers with grief. Emily Mary Osborn’s The Governess (1860) silently bears the scolding of a cruel mistress flanked by a gaggle of spoiled brats. By contrast, even in her mourning dress, Solomon’s governess does not appear to be grieving. There’s something more severe in her stare.

Solomon never worked as a governess, although she likely felt some degree of camaraderie with women who did. Like the majority of governesses, Solomon was an unmarried middle-class woman who worked to survive. Had she felt only condescending pity towards governesses, it’s unlikely she would have imbued her artwork and its subject with such emotional complexity.3

That her governess has a more obviously complex inner life than the blankly cheery lady of the house also strikes me as no accident. Solomon came from a well-connected and reasonably affluent family. Nothing in the historical record indicates a suitable match and comfortable married life were beyond her reach. Instead, it appears she deliberately chose not to marry and have children in order to be an artist. Women in their early twenties who make this choice tend to feel some sense of superiority over women who choose the opposite.4 The aspiring young woman artist imagines whatever suffering her choice brings will be inherently more noble than whatever may befall her wife-and-mother opposite, especially if what befalls said wife and mother is domestic bliss. Nothing could be more unforgivably trite.

There’s an indignation to The Governess that feels autobiographical—self-congratulatory, even. The governess may be unhappy, but she is far more interesting than her pink-clad counterpart. We project far less onto the lady, who is a caricature of the perfectly fulfilled and meaninglessly content Victorian wife and mother. All happy married ladies are alike, The Governess insists, and therefore boring. But each unhappy (artist-disguised-as-)governess is unhappy in her own way, and therefore compelling.

Like many governesses, Solomon’s eventual destitution was caused by her relationship to a family, albeit her own. In 1873, her younger brother Simeon was arrested for solicitation and sodomy in a public toilet. It destroyed the family’s reputation, and by 1879, she was financially ruined. In a letter to the poet and painter Dante Rossetti, she attributed both her “great difficulties in a monetary way” and “embarrassments” to “a severe family trouble [that] I believe… you know of.”5

According to an early edition of The Dictionary of National Biography, these embarrassments led her to develop “an errant nature and come to disaster” at the end of her life.6 Her so-called errant nature—a typically British euphemism for severe alcoholism—may have been more an exaggerated tidbit of artist-circle gossip than actual fact, but the disaster she came to was real. Solomon was hit by a horse-drawn cab crossing Euston Road in Central London and died of her injuries on November 20, 1886. To date, The Governess remains in a private collection.

Einbund, Spencer. “The Times, Jane Eyre, and the Governness.” The Victorian Web, 18 May 2010, victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/governess2.html.

Some art historians interpret the happy couple as the daughter of the house and a gentleman caller instead of master and mistress. This interpretation does not meaningfully change the core of my argument; the daughter being actively courted is simply a wife and mother in waiting.

With the caveat that Charlotte Brontë did in fact work as a governess, I would argue that the exact same could be said about her as it relates to Jane Eyre.

This is not exclusive to the Victorian era or young women or aspiring artists. See also: r/childfree.

Rossetti most certainly did know. He joked about Simeon changing his name to a pun on “buggerer” in a letter to the art dealer Charles Augustus Howell written the same year.

Quotes in this paragraph sourced from: Round, Alex. “Rebecca Solomon as a Social Activist.” Victorianweb.org, 14 Sept. 2021, victorianweb.org/painting/solomonr/round.html.

Quote sourced from catalog entry for Christie’s Live Action 7417 - Victorian & Traditionalist Pictures (7 June 2007): https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4928785

Please make a crop top that reads “the crop job makes it bitchier.” I will buy one and wear it all summer long.

There’s such scandal about a man being cuckolded into caring for another man’s biological child: so ‘unnatural’…

Yet women are assumed to be born to care for other women's brats as part of destiny. Why the discrepancy? Still!

This “side eye”* Governess does seem to be only going through the motions of matronly warmth herself; a cold hand lightly on the child’s shoulder.

I’m not a jewelry scholar, but if the lady in pink is married to the much older man, wouldn’t her very obvious left hand be wearing the ring on the ‘ring finger’?

* great description! Really brings her to life. Well done, thank you!