I first clap eyes on Hungary through the window of a wobbly train car chugging over its northern border. The landscape is not much to look at, although neither is my notebook, where several idle sketches of the Venus of Willendorf hover beside a list of half-formed ideas about female archetypes. Since there’s no internet on the train I’ve jotted down a reminder to Google the plural of the word Venus. (I guess Veni. It will turn out to be Venuses.) A girl my age, maybe a tad younger, sits across from me and watches as I botch the proportions of Lust from Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze. She is visibly unimpressed. That makes two of us.

As foretold by the rather insistent reminder emails I’ve been deleting every day for the last week, the train stops 30 miles west of Budapest in Tatabánya. Something to do with construction work, I think, never having read much further than the subject line. Tatabánya’s train station consists of a few rows of exposed platforms linked by leaking elevated walkways and a rectangular building of flat glass and dark green painted steel. On the street-facing side a line of arches runs through the empty plaza, each one topped by a round lantern hovering in the middle of a wide ring so as to resemble Saturn. The station is decrepit in that deflated but still-functional way oddly specific to tourist-free cities in the former Eastern Bloc. It’s like porn, in that you know it when you see it.

More and more I’ve gone looking for it. As an American who a) missed the Cold War, b) owns well-thumbed copies of both The Gulag Archipelago (the abridged version, I don’t deny it) and Kropotkin’s Anarchist Communism, c) has spun many times ‘round the leftist ideology carousel, d) has felt irreversibly politically alienated by my own government ever since the DNC closed ranks around Hillary during the 2016 primary to our collective peril, and e) considers the Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed monograph an acceptable Christmas gift, my fascination with the remnants of the USSR and decaying Soviet astro-futurist-optimist design wherever I encounter it can only be described as on-brand. In other words, having been born to The Other Team after 1989 but now ambivalent at best to its Cold-War-winning national (economic) ideologies, I can’t help but find Soviet public art fascinatingly alien. (Later on, a mural of Sputnik soaring over a cluster of multiethnic women workers will be the lone highlight of an otherwise miserable night in Bratislava.) It’s all so irresistibly loaded with low-hanging symbolic fruit in the context of its own material decline. All that remains of a nation’s great interstellar dream is a fading mural in a train station… The Saturn-shaped street lamps still glow, even after the cosmonauts have all gone extinct… I’ve got more where those came from. This shit writes itself.

An hour or so later the replacement bus service dumps us off in Budapest. I spend roughly 30 seconds playing touchscreen roulette with the subway ticket machine before admitting defeat and calling a ride. The driver has a buzzcut and is good-looking in a jarhead sort of way and the radio station plays Top 40 hits from 18 months ago. As the Danube comes into view I think primarily about how nice peeling off my jeans will feel. They are fast approaching the end of their socially-acceptable-to-wear-without-washing window.

Most of what I know about Hungarian history is the part that happened to coincide with the lifetime of Empress Elisabeth of Austria, Hungary’s former queen, biggest fan, and a subject of persistent fascination. I know it was one of those unlucky countries that took the 20th century jab-cross of German-then-Soviet domination on the chin. And I know enough to keep myself from cracking open Viktor Orbán’s Wikipedia page while here, lest I rub the rose-colored tint off my metaphorical glasses. That’s about it.

I’m also not looking for anything in particular in Hungary. The night I arrive I read Portnoy’s Complaint over roasted duck in red wine sauce as recommended by the waiter. When he asks me what I’m doing in Budapest, I answer, “I don’t really know,” and we both laugh awkwardly.

The following morning I decide to go to Franz Liszt’s former residence. Am I overly familiar with the composer? No. But Ken Russell’s Lisztomania is an essential entry in my high camp cinematic canon—Roger Daltrey plays Liszt, Ringo plays the Pope, and Richard Wagner is depicted as zombie Hitler who mows down crowds with an electric guitar that doubles as a machine gun—and how different can the real thing be, really?

Am I kidding? Yes. (Not about Lisztomania, though. That’s very real.) Is the Liszt Museum pleasant enough? Also yes. I admire the blue wallpaper in the salon and his ornate silver music stand crowned by three glowering Ken-doll-sized busts of Beethoven, Weber, and Schubert. On my way out I spot a poster advertising a morning piano concert in the small performance hall next door. It’s 40 minutes from now. I have no plans, which means I now have 40 minutes to burn.

Opposite the Liszt Museum on Andrássy Avenue—Budapest’s version of the grand European urban boulevard lined with designer boutiques and embassies and an opera house—sits the one-time headquarters of the Arrow Cross Party and the Államvédelmi Hatóság. The former led Hungary’s short-lived collaborationist government from October 1944 to March 1945; many of its senior members were tried and executed as war criminals following the Axis surrender. The latter, abbreviated ÁVH, acted as the Hungarian equivalent of the KGB from 1945 until its official dissolution in 1956. The building was renovated into a remembrance museum memorializing victims of both regimes and rechristened the House of Terror in 2002.

Remembrance museums tend to be choose-your-own-adventure in terms of time commitment, so I figure now is the time. Not going was never an option anyway. Inside are some of the most perplexingly organized, bewilderingly surrealistic, and ideologically confused exhibitions I’ve ever encountered, all lorded over by Budapest’s surliest museum staff. (Their indefatigable churlishness does match the mood, I suppose.) In one room, the face of Ferenc Szálasi, leader of the Arrow Cross Party and, briefly, the country is projected onto the blank sack head of a uniformed mannequin. The effect is that of an effigy awaiting the flame. There’s a maze-like hall constructed from bricks of fake pork fat indented with the words “1 KG SERTÉZSÍR,” upon which the receipts of state seizures of agricultural products are hung. I am unsurprised to later find internet confirmation of my suspicions that the museum is politically controversial in its contextualization and interpretation of history and tyranny.

Visit enough of these places and you’ll recognize a few consistencies among them. For one—and maybe I’m being coarse here, but it’s as typical of 20th century memorial museums as it is of above-average horror movies—the main attraction is located in the basement. No self-respecting totalitarian regime tortures above ground, and it’s the eerie horror-drama of padded cells and interrogation rooms that sells tickets, not the promise of viewing agricultural receipts.

The House of Terror’s subterranean jail cells are mostly empty, awash in cold daylight filtering through the bars of the street-level windows perpendicular to the ceiling. One corridor dead-ends into a closet-sized room containing a gallows, visible only once you cross its threshold. As far as visceral museum jump scares go, it works. A nearby sign admits the gallows was actually brought over from an entirely unrelated penitentiary on the southeast side of the city, but you’re meant to read that only after seeing the gallows, and I do.

I check my phone. The concert starts in ten minutes. Despite the museum-studies-flavored ambivalence nagging at my every thought, my throat is starting to constrict and I’m not sorry to have to leave. I take the stairs two at a time and dash back over to Liszt’s apartments, where I’m let into the small concert hall for free. I expected to pay, and I don’t understand why I don’t have to, but that level of detail well exceeds the load-bearing capacity of the pidgin German the ticket lady and I speak at each other between apologetic smiles.

I sit towards the back and steal several needlessly furtive glances at the program pinched between the fingers of the older man to my right. Out of the stage door emerge two pianists: a middle-aged woman in a sparkly black sleeveless top, and a portly, stern-looking man with glasses. They launch into Mozart’s Sonata for Piano Four-Hands in D major while I pray to be delivered via nose-blindness from the powdery perfume of the woman to my left who is otherwise quite lovely. A sizable painting by Sandor Liezen-Mayer serves as a backdrop, its baroque smorgasbord of Greco-Roman gods and cherubs gallivanting gaily through the heavens. Allegorical, obviously. Of what exactly, I’m not so sure.

It’s at this point that I marvel at how quickly I transited the entire gulf between abject if systematic barbarism and high art in search of eternity. I seem to have leapt from the extrajudicial murder of political prisoners to Schubert’s eminently pleasant Variations in B-flat Major in a single bound. It couldn’t have taken more than three minutes, counting the time spent waiting at the crosswalk. How peculiar.

I’ll get used to this sensation, in a way. The uncanny ease with which beauty and terror coexist and cohabitate in Budapest—indeed the ease with which they achieve near-total reconciliation with one another, over and over—comes to form my lasting and most potent impression of the city. It doesn’t take long before I start seeking the phenomenon out in the corresponding national galleries. I trudge determinedly from painting to painting much to the chagrin of my aching left ankle, braced so as to prevent a repeat of the sprain that flung me to the sidewalk outside of the Assemblée nationale after too many cigarettes but a defendable amount of champagne as the sun set behind the Pont Alexandre III on one of those summer evenings where Paris arranges itself into such a stereotypically gorgeous tableau that it would border on parody were it not so ravishing.

But this isn’t about Paris, and Budapest is no Paris, and thank Hungarian God for that. One Paris is sufficient, even for me. To be fair, French aesthetic sensibilities did make a cameo via a temporary Renoir exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts. With the exception of the coolly serene Young Boy with a Cat, however, I’m afraid said exhibition made a rather strong case for the Renoir sucks at painting people, tedious as they are. (Ok, this was my last French digression. At least until next week.)

In Budapest I found a version of beauty that is often inseparable from terror and suffering and ugliness and sheer intensity of feeling, and it’s remarkable how comfortably and matter-of-factly these elements live alongside one another and even fuse together in Hungarian art. Hungarian art has embraced the grotesque, and I mean that in the traditional sense of simultaneously invoking disgust and fascination and pity. Beauty is distorted in a way that nevertheless appeals. Despair, poverty, tragedy, and injustice are aestheticized and depicted in a way that neither trivializes nor renders them repugnant.

I sensed this keenly on the top floor of the Museum of Fine Arts, far from Renoir’s too-pink gobs of absurdly proportioned impressionistic flesh. The bottom half of a beguiling wall decoration from the late 18th century was dominated by Louis II tumbling to his death during the Battle of Mohács in 1526. This was nothing short of a lament. The Ottoman victory plunged the Kingdom of Hungary into political chaos, its territory subsequently divided among Transylvanian, Habsburg, and Ottoman control. The effects and borders of this partitioning would last centuries.

Nearby aristocratic portraits were united in their stubborn rejection of any uniform conception of beauty as marked by flawlessness or indicative of holiness. A 1690 portrait of Princess Pál Esterházy makes her look terribly plain, with a descending jowl and asymmetrical eyes. Noblewomen dripping in finery sported lumpy moles. A 17th century image of Saint Elizabeth makes her almost as ugly as the pathetic beggar at her feet. Stubby noses craned over bloated chins. Eyes bugged out of shadowy recesses in pudgy cheeks.

Later on in the Hungarian National Gallery, I discovered Hungarian artists’ fixation on depravity, loneliness, isolation, persecution, subjugation, and corruption hit a fever pitch at the turn of the 20th century. In Károly Ferenczy’s Joseph Sold into Slavery by His Brothers (1900), the biblical runt gazes out at the viewer, half-naked and held upright by his brothers, his unfocused eyes and limp wrists making him appear almost anesthetized. The twisted faces of children with bulging eyes and gaping mouths dominate the foreground of an 1899 study by Simon Hollósy for The Rákóczi-March. Painted in loose, uneven strokes, their bodies dissolve into phantasms near the frame. There is nothing Christmas-y about the three stone-faced men wordlessly gathered around a table in István Réti’s Christmas Eve of the Bohemians Away From Home (1893). The yellow light at the center of István Csók’s Orphans is swallowed by the deep, desolate blues that surround the two young women seated at a table, one either too tired or too inconsolable to lift her head from its surface.

It all came together in Lázló Tóth’s double-edged Beauty, Wealth, Intellect triptych (1894). Each panel presented its subject with traditional discipline but seething cynicism. Beauty depicts a prostituted woman, her white stole and pale face set against the thick darkness of her coat and the city street. In Wealth an old crone tempts a young woman with a bauble while stockbrokers mill in the background beneath a golden calf. And in Intellect, a young man pours a solution into a test tube, looking every inch a paragon of intellectual curiosity until closer examination reveals that he’s an anarchist making explosives. “With this symbolic, allegorical composition,” reads the wall text, “the painter, who died at a tragically young age, painted an ‘altarpiece’ for a world turned inside-out.”

Was it a world turned inside-out? Or was it an inside-out depiction of the world as it was? Had the lofty ideals of beauty, wealth, and intellect ever existed in some purified form independent of their dark undersides as seen by Tóth? There’s a frankness to Hungarian painting, one that doesn’t depend on the denial of beauty, per se.

I thought again of the frankly rendered aristocratic portraits in front of Jenő Gyárfás’ The Ordeal of the Bier. Based on a scene from a dramatic ballad, the painting’s central figure, Abigél Kund, descends the stairs leading into a darkened room where her dead lover lies on a slab. Gyárfás captures her as she realizes she is inadvertently responsible for his death. His Abigél claws at her own hair in stunned agony. Her expression somehow hangs between total incredulity and the brute shock of realization. Her face is lit as brightly as her lacy white dress, which drapes elegantly in wide folds that descend from a decorative gold chain at her waist. She simultaneously wears an almost animalistic expression of grief and a dress that projects fashionable and sophisticated elegance—beauty and terror manifesting, colliding, becoming one.

Elsewhere from Gyula Derkovits, both from 1930: the hard and inquisitive stare of the reader’s companion in Writ, and the heaping mass of a man in Fishmonger, hands the size of baseball mitts brandishing a blade like he intends to use it on something other than the inert gray fish. Faceless but no less arresting for it is János Vasari’s captivating Golgotha (Christ on the Cross) from 1930. Its forced perspective positions us to gaze down on the sagging body of the crucified Christ, ghostly white save for streaks of red blood running down his torso and legs.

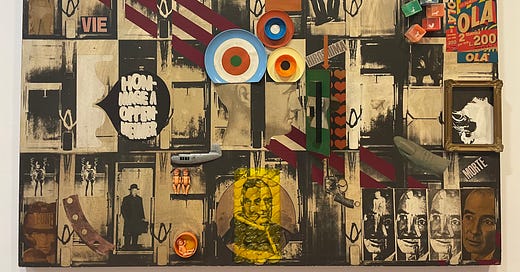

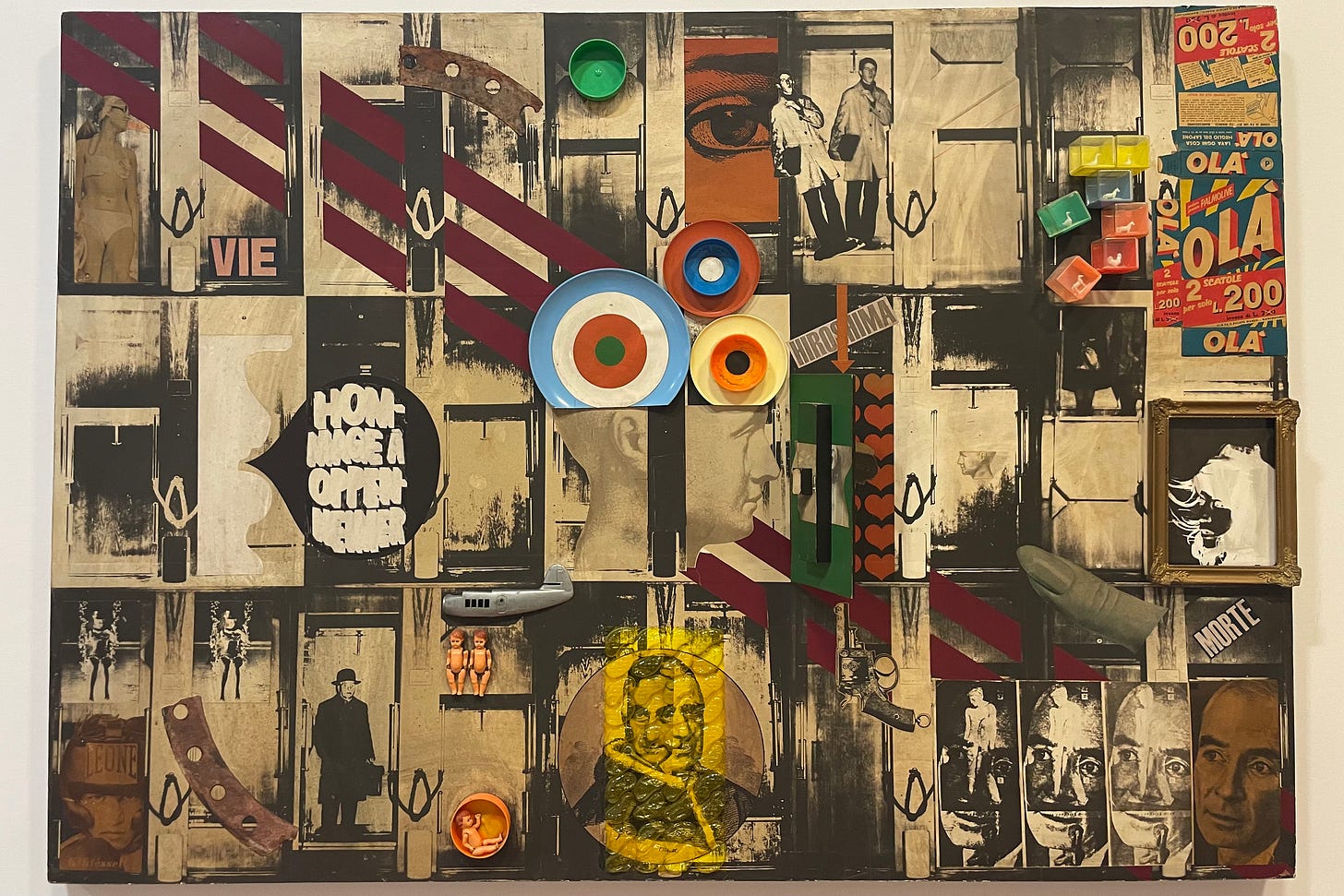

The twisted march continues into the contemporary. Throne of Fire (The Execution of Dózsa) dominates the top floor of the gallery. Completed in 1972, Tibor Szervátiusz’s gigantic sculpture depicts the skeletal remains of militant rebel György Dózsa, gruesomely executed in 1514 for leading a thwarted peasant uprising. It’s as frightening as any fantastical monster but just as evidently the victim of some terrible dismemberment. Its legs end at the knees; one spindly hand clutches the opposite detached forearm by the wrist. György Kemény’s graphic, almost playful Homage à Oppenheimer (c. 1967-68) includes a mushroom cloud cut-and-pasted over a pattern of plump red hearts and a silkscreen repetition of the scientist as shamelessly pop as any of Warhol’s portraits of Elvis. In a special exhibition I find myself taken with Ágnes Uray-Szépfalvi’s Slap (1999), which channels the same vague old Hollywood aesthetic as Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills. It’s rife with ambivalence. It feels definitive yet momentary as a snapshot. It is not the moment of the slap but a split second after making contact, the female victim’s expression readable as either pain and pleasure.

The presence of the grotesque in works deemed representative enough of Hungarian art to land in a national gallery is so insistent and varied that I find myself missing it when it is absent. Take Pál Szinyei Merse’s Picnic in May (1873), for instance, which the wall text describes as “one of the best-known and most important works of Hungarian painting” but strikes me as a middlingly provincial picnicking scene vacant the appeal of its topical (French) siblings—i.e. the enticing and casually confrontational gazes of Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, the flawless composition and irrepressible delight of Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party, or even the incidental splendor of Monet’s unfinished Luncheon on the Grass, painted in response to Manet’s work. The wall text says Picnic in May was derided by critics at the time as “dreadfully prosaic,” implication being that this was a gross misjudgement. I am, however, inclined to agree.

It’s evening when I leave the National Gallery. The sharpened neo-Gothic spires of the Parliament building glisten in the reflection of the Danube, and an enormous yellow moon is rising steadily over the tips of St. Stephen’s Basilica. I lean against a railing and nearly applaud when it slips free of the last wisp of cloud. If anyone else feels similarly compelled they don’t show it. It’s like at the concert that morning, dutifully waiting for others to clap first.

It doesn’t matter. There are no cosmonauts left to hear it anyway… I descend the hill and cross from Buda to Pest. Mozart, the moon, the whole thrust of beauty and terror in Budapest—to move among them in the space of a day is, I think, more than enough.